If we look at the first major video game, Pong, we can see that the core of a video game looks very different from other media forms predicated primarily on storytelling. However, in the same way in which elements of play can be tapped to expand a story world, much of the evolution of video games too has come from learning how to informatively integrate elements of storytelling. This is not to say that any incorporation of story elements into a video game guarantees improvement. On the contrary, many superficial attempts to do so have failed almost as badly as the early edutainment attempts to integrate learning and games. However, if we look at timeline of many of the major milestones in the evolution of the video game medium, we see repeated cases where the most popular game of a particular time period was one that explored creative ways of incorporating story elements into a game world.

|

|

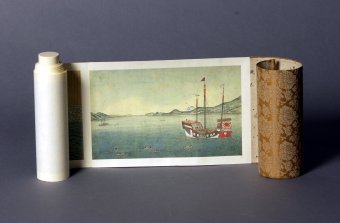

| A Japanese scroll from the Claire County library tells a story as the reader rolls the scroll through images of a series of locations. | The player in Super Mario Brothers explores a fantasy universe by scrolling through the world. [Source] |

![]() Games as a Narrative Architecture -- Spatial storytelling [External Link]

Games as a Narrative Architecture -- Spatial storytelling [External Link]

Whereas many of the earlier games sustained themselves primarily on elements of action, role playing games such as the Final Fantasy series use character development as their primary game mechanic. Characters in these games are portrayed as having numerous attributes and skills which the player develops through the course of the game. The game then becomes about the journey characters take while developing from a novice adventurer into a specialized and powerful hero. Many of the Final Fantasy titles include numerous cinematic elements and develop complex character relationships.

Whereas many of the earlier games sustained themselves primarily on elements of action, role playing games such as the Final Fantasy series use character development as their primary game mechanic. Characters in these games are portrayed as having numerous attributes and skills which the player develops through the course of the game. The game then becomes about the journey characters take while developing from a novice adventurer into a specialized and powerful hero. Many of the Final Fantasy titles include numerous cinematic elements and develop complex character relationships.

![]() More Narrative elements in the Final Fantasy series [external link]

More Narrative elements in the Final Fantasy series [external link]

One of the most popular computer game series of the early nineties, Wing Commander featured live actors such as Mark Hamill (Luke Skywalker in Star Wars), Tom Wilson (Back to the Future) and Malcolm McDowell. Described as "interactive cinema", Wing Commander marked one of the most direct attempts to incorporate traditional storytelling into a video game.

One of the most popular computer game series of the early nineties, Wing Commander featured live actors such as Mark Hamill (Luke Skywalker in Star Wars), Tom Wilson (Back to the Future) and Malcolm McDowell. Described as "interactive cinema", Wing Commander marked one of the most direct attempts to incorporate traditional storytelling into a video game.

In the world of Myst, players began the game by opening a book which magically transported them inside of it. With a narrative complexity so rich it was used in literature classrooms, traditional game enthusiasts first found Myst to be "basically, a decent looking slide-show with some primitive FMV sequences, exhausting puzzles and intricate layers of back-story that only the most dedicated of fans will be patient enough to sift through." Ultimately, however, Myst's compelling integration of rich story elements into a game experience helped it become the best selling PC game up until the release of The Sims.

In the world of Myst, players began the game by opening a book which magically transported them inside of it. With a narrative complexity so rich it was used in literature classrooms, traditional game enthusiasts first found Myst to be "basically, a decent looking slide-show with some primitive FMV sequences, exhausting puzzles and intricate layers of back-story that only the most dedicated of fans will be patient enough to sift through." Ultimately, however, Myst's compelling integration of rich story elements into a game experience helped it become the best selling PC game up until the release of The Sims.

![]() NeoPets Overview and Discussion

NeoPets Overview and Discussion

A game built directly on web technologies, Neopets design allows it to easily mix a variety of web activities into its game world. As Seiter describes:

Neopets capitalizes on every genre of fan art and fiction popularized around television in the last twenty-five years and widely disseminated through the Internet (Seiter 1999). On the Web, these varieties of expression are accumulated and sent out to audiences far larger than that of traditional fan associations, newsletters, and 'zines. Neopets publishes a weekly online newspaper, which offers opportunities to publish short stories, drawings and paintings, poetry, news stories, strategy tips, and personal testimonials on the Web. While to a nonfan these look like kitsch, and many are blatantly juvenile, they are carefully blended with the site's own official publications -- such as the Neopian Times and its promotional materials describing the history of Neopia. A fan's poem describes the emotional identification with virtual pets, and exemplifies the way that Neopets have fit well into a girl's fantasy genre:

The Lonely Aisha -- By venuslovegoddess16

As you walk through

The rubbish littered street

You see her up ahead

There she lies, sad and dirty

With nothing but papers for a bed

She doesn't wag her tail

Or run to you with glee

For in her eyes

There's a glint of sadness

Which we pretend we can't see ...

You take from your pocket

A collar and lead

And when she looks at you with love

You know you've helped a pet in need

So always adopt

If you can afford the cost

Because they're the pets

That need you most

The pets that are sad and lost

Besides the integration of player composed stories, games like Neopets and Animal crossing are interesting in how they are able to tell stories over time. Games such as Pong would begin when the player loaded the game and end when they turned the game off. If a player came back to the game the next day, the game would start from scratch and they would repeat the same experience. Later games allowed players to save their game state before quitting; however, when the player returned the game would remain essentially unchanged from where they had left. In games such as Neopets and Animal Crossing, however, characters in the game continue to develop their virtual lives while the player is away -- requiring them to explore any new developments when they return. For example, if a Neopets player neglects their pet for too long, they become irritated and hungry. When a player returns they need to feed their pet and deal with their irritation.

While all of the top selling video games of the last twenty years have been titles that explored innovative ways of integrating creative story elements into a game world, The Sims 2 provides an exceptionally rich example in which multiple levels of storytelling elements are layered upon one another. At the highest level, the game itself can be seen as a form of emergent narrative.

Will Wright [designer of The Sims Series] frequently describes The Sims as a sandbox or dollhouse game, suggesting that it should be understood as a kind of authoring environment within which players can define their own goals and write their own stories. Yet, unlike Microsoft Word, the game doesn't open on a blank screen. Most players come away from spending time with The Sims with some degree of narrative satisfaction. Wright has created a world ripe with narrative possibilities, where each design decision has been made with an eye towards increasing the prospects of interpersonal romance or conflict ...

Games as a Narrative Architecture -- Emergent Narratives [External Link]

When looking at video games, or any media, it is important to recognize that what a player decides to do with a game may ultimately have nothing to do with how the designer intended the game to be played. In the popular shooting game Halo 2, the designers included a "record" feature to give players the chance to review their games. Some players, however, chose to use this feature to create a four season DVD comedic narrative. Others went so far as editing the game's program code to make it more amenable to their storytelling needs.

(Wright)

Although the original Sims game did ship with rudimentary storytelling tools, the complexity of player authored stories far exceeded the designers expectations. When planning The Sims 2, the designers worked to include a full suite of storytelling tools directly in the game. As a result, many players of The Sims 2 are independently motivated to author elaborate stories about the lives of their characters in either text or movie format. For teachers searching to find ways to motivate kids to write stories in foreign languages, the narrative support provided by emergent narratives like The Sims 2 provides a perfect catalyst to encourage student writing.

(Wright)

By combining existing rich narratives with an open-ended game framework, The Sims 2 offers players (or students) enough narrative elements that they should have little difficulty imagining an engaging story to tell, yet still gives them an active role in the actual construction of that story. Additionally, it provides motivation for the students to better understand the narrative elements from the original story. Both of these properties should be especially interesting for Foreign Language educators looking for activities to integrate with classic plays in the L2.

![]() Transmedia Storytelling with The Sims 2

Transmedia Storytelling with The Sims 2

![]() More about Narrative in Games [External Link]

More about Narrative in Games [External Link]

To be fair, only looking only at the most successful video games somewhat skews the larger picture of storytelling in video games. As mentioned earlier, many superficial attempts to meld story and video games have failed almost as badly as the early edutainment attempts to meld learning and games. As one well respected game designer describes:

The commonest route these days for developing games involves grafting a story onto them. But most video game developers take a (usually mediocre) story and put little game obstacles all through it. It's as if we are requiring the player to solve a crossword puzzle in order to turn the page to get more of the novel.

By and large, people don't play games because of the stories. The stories that wrap the games are usually side dishes for the brain. For one thing, it's damn rare to see a game story written by an actual writer. As a result, they are usually around the high-school level of literary sophistication at best. (Koster)

Logically, we can see why instead of switching back and forth between playing a great game and watching a mediocre story, one would prefer to simply play a great game and then independently go off afterwards and watch a great movie. Even if someone was to take the effort to make a great game interleaved with a great story, that still would not necessarily be any more compelling an experience than first playing a great game and then watching a great movie afterwards. For many game designers, this has lead them to the conclusion that they should abandon storytelling altogether -- or at least relegate it to a minor enough role where it doesn't compete with the game experience. If we look at a game like Tetris, we can see that it is certainly possible to create a great game with little or no storytelling elements.

Looking broadly at the game industry today, we are left with an interesting stratification. At the bottom are games in which traditional stories are simply interspliced inside a game, or where the objective of the game is simply to replay the plot of a story. In the middle we have games where, relative to the gameplay, story elements are basically ignored. And finally, on the very top, we have those games that find innovative ways to tap into elements of storytelling in order to create richer game worlds -- such as those outlined above.

For those interested in educational games, it is important to understand this stratification and why some attempts at integrating story elements into games succeed while others fail, as this provides a useful model when attempting to integrate learning elements into games. For foreign language educators in particular, as so much of our existing pedagogy is built directly on top of storytelling, it is crucial that we do not repeat the mistakes of so many games already out there.

To examine this fully, we should first define terms such as 'games', 'play' and 'story.' Unfortunately, these are all terms that are currently being fiercely debated with no agreed upon definitions. For now, it is perhaps most productive to consider that there is an as-of-yet undefined experience we call 'play' which is shared among all human beings. Looking neurologically, we could guess that this might someday be seen as experiences that tap into the ways in which human beings are designed for solving problems (in the loosest sense of the word: motor coordination problems, spatial problems, social coordination problems, logic problems, constraint problems, etc). Distinct (but by no means exclusive) to that is an experience we call 'story.' Looking neurologically, we could guess that this might someday be seen as related to an organizational structure well suited for connecting human experiential memory with imagination.

![]() (see schema theory and connectionism) [alias]

(see schema theory and connectionism) [alias]

If we accept that these can be thought of as two distinct experiences, then switching back and forth between the two does not give us any benefits over simply sticking with one or the other. Certainly, if somebody is an expert at understanding play, it will be more advantages for them to stick with creating a great play experience rather than trying to also design a story experience. In theory, though, being able to tap into both at the same time would give an additive bonus.

Unfortunately, the way mainstream storytelling has developed for media forms such as television, movies and novels makes it impossible to transpose directly into a play experience:

From a design viewpoint the dramatic arc (and its associated character development) is the central scaffolding around which story is built. The characters that we become immersed in as an audience are inextricably moving through a linear sequence of events that are designed to evoke maximum emotional involvement. Everything else (setting, mood, world) is free to be molded around this scaffolding. They are subservient to it. The story is free to dictate the design of the world in which it occurs.

A game is structured quite differently. The paramount constructs here are the constraints on the player. As a game designer I try to envision an interesting landscape of possibilities to drop the player into and then design the constraints of the world to keep them there. Within this space the landscape of possibilities (and challenges) need to be interesting, varied, and plausible (imagine a well-crafted botanical garden). It is within this defined space that players will move, and hence define their own story arc ...

However, if instead of directly transferring storytelling as it has developed for other media into video games, we return to storytelling simply as a shared experience enjoyed by human beings, we can then begin to reconstruct a new set of elements capable of tapping into the story experience that can also operate within a play environment.

My aspirations for this new form are not about telling better stories but about allowing players to “play” better stories within these artificial worlds. The role of the designer becomes trying to best leverage the agency of the player in finding dramatic and interesting paths through this space. Likewise, I think that placing character design and development in the player’s hands rather than the designer’s will lead to a much richer future for this new medium. (Wright)

If we are to reconstruct a set of storytelling elements such that they will be able to operate within a play environment, we might start by re-thinking our notions of authorship. The first piece we need to recognize is that the creation of a story relies on a minimum of two authors: the reader and the writer. In a novel, the writer creates a plot direction, the reader creates a visual image of the plot. In a movie, we are provided with a visual image of what is in front of the camera, but the viewer authors everything that happens outside the view of the camera.

(Wright)

When creating stories inside video games, we need to reconsider what elements of novels that have traditionally left to the reader to author could instead be authored by the game design team, and which elements in novels that have traditionally been created by the writer could instead be authored by the player.

(Wright)

Next we need to think about what is common in storytelling across media forms and use that as a starting point for constructing a story within a game. Perhaps the best common element to use as a starting point is that video games, movies and novels all create fictional worlds. (see also Jenkins)

(Wright)

Finally, for those trying to integrate a game with an existing story (I.E. The Little Prince), it is necessary to think through which aspects of the story are already provided by the initial stories and what new directions could be achieved by a game. Ultimately, the two should work together to create a "parallel exploration of a story space."

(Wright)